A Little Not-music

So, challenged by our savage to produce yet another work of genius, I have translated another poem by Cao Cao, if only to prove that I can do it. Admittedly, after studying it some, I like it more than the tortoise poem--which, I don't really like all that much. The original can be found in Liansu's comment on my previous post, so I won't bother reproducing it here.

I must say, I found translating this a bit taxing, and not merely because Classical Chinese is not one of my better languages. It has certain musical features that I would love to reproduce but invariably can't. The repetitive adjectives in certain lines (e.g. "bright so bright the moon") are meant approximate the repeated syllables in Chinese, but I just can't manage the internal rhyme.

I must say, I found translating this a bit taxing, and not merely because Classical Chinese is not one of my better languages. It has certain musical features that I would love to reproduce but invariably can't. The repetitive adjectives in certain lines (e.g. "bright so bright the moon") are meant approximate the repeated syllables in Chinese, but I just can't manage the internal rhyme.So, thinking about what Liansu said about the kind of language used, I tried translating it into an affected Elizabethan English. The result was monstrous, because Classical Chinese tends toward the spare and direct where The Queene's Anglishe is ornate and oblique. So, instead I decided to go back to the alliterative style common in Old English, even reproducing the caesura that I felt roughly approximated the pause in the Chinese lines. I'm not certain I succeeded to any significant degree--I'm certain the Savage Sinologist will let us know--but if nothing else the lines "from far and wide / we gather together / to rest and rehearse / the rites of our friendship" are some of the best I've ever produced.

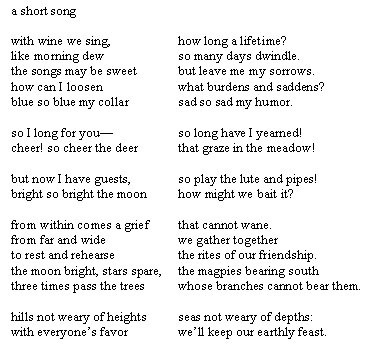

N.B. I apologize for the picture of the text; I couldn't for the life of me get the html to do what I wanted it to.

7 Comments:

"And then went down to the ship", bitch!

Hey, I actually like this.

"how can I loosen / what burdens and saddens? // ... from within comes a grief / that cannot wane."

Clearly along with being a badass warlord, Cao Cao was a grad student in Comp Lit at some point.

Or, Mike, along with being a grad student in Complit, you actually were a badass warlord at some point.

I love your translation too Nicholas despite your constant insults/compliments. "from within comes a grief / that cannot wane." Mike has a good reason to like this line. You know how rare it is to have a translation convey exactly what is in the original both in meaning and in effect. However, yes, there is always a however, but I need some sleep now before I could continue :-)

You know, I always kind of wondered why I've been carrying around this heavy dose of Nietzschean master-morality with me, despite my secular, but implicitly Lutheran upbringing. It all makes sense now - I used to pillage thousands of commoners in East Asia! Thanks Liansu!!!

However, we encounter the never-ending dilemma in translation. How do we deal with the shadows of history that give the poetry so much richness? Explaining the story behind each allusion will eventually lead to a recounting of all stories, which will totally overshadow poetry itself. Besides, the power of poetry often lies in the shadows hovering far off. Magic breaks and shadows die when there is too much light. Not to say bad story telling will totally ruin the poetry.

Some thoughts:

慨当以慷 gives me more of a heroic but sad feeling than sweet.

“how can I loosen/what burdens and saddens?” is the best translation for何以解忧?but you left out 唯有杜康, the answer to the question, my favorite line。杜康 (Du Kang): legend has it that Du Kang was the first person who ever made wine, the best wine ever. So “Du Kang” became another name for the best wine. Using “Du Kang” rather than “the best wine” naturally lead our imagination back to the beginning of the mythical history, making “what burdens and saddens” heavier than what a Complit grad student usually bear

青青子衿: 子 means “you or your.” 青, this one character could be green, blue or black in Chinese. When referring to dress, most books agree that it means black. Intellectuals in Zhou Dynasty usually wear robe with black collar. So here Cao Cao is directly addressing talented intellectuals such as you and Mike whom he would need to unify China.

“the moon bright, stars spare/ the magpies bearing south” is another near perfect translation of the original line. I especially like “stars spare,” captured both the succinctness and the alliteration in the original. Nobody is sure though whether 乌鹊 is crows, magpies, both, or wild geese. Some even translated it as “crows and magpies flying south.” What the heck?! But the other day when I was walking back home I looked into the sky, I saw the exact picture Cao Cao depicted. I could not tell whether the flying objects were wild geese, crows or whatever. It suddenly occurred to me that maybe Cao Cao was simply using the literal meaning “dark birds.”

Got to stop for now. Damn, my comment is again longer than your post!

For the most part, Liansu, I agree with your assessment. My habit, and it's probably not a good one, with old poetry is to strip away really involved allusions. I actually knew who Du Kang was, but thought that a random name coming out of nowhere wouldn't really help an English perceive the consistent turning from interior to exterior that the poem enacts.

In choosing between green and blue for 青, I chose blue because of the twinge of melancholy it carries with it. I didn't know it could mean black. "my" is a stupid typo, of course 子 means "you."

Nicholas, yeah, I know. And you know it is always easier to be a critic than an author:-)

btw, I wrote to T about the rescheduling of my topics paper defense and he was totally pissed off. So Nicholas and Mike, did you hear anything from him about your defense? Sorry Nicholas for using your space like this. Mike is at least partly responsible for this. He insists on barring anonymous posts from his blog.

Very pretty site! Keep working. thnx!

»

Post a Comment

<< Home