Telling Time

So, a few weeks ago I took a trip to Hiroshima or rather more specifically to the largest island in the bay Hiroshima overlooks, Miyajima. Suffice it to say, after dining on an exquisite array of ryokan food (which along with public bathing seems to always be a mandatory part of your stay), avoiding molestation by sacred deer permitted to roam willy-nilly about the town, and perusing such wonderful oddities as the world's largest rice paddle and poetry written on liquor bottles, we headed into Hiroshima proper to go to the Peace Park and museum.

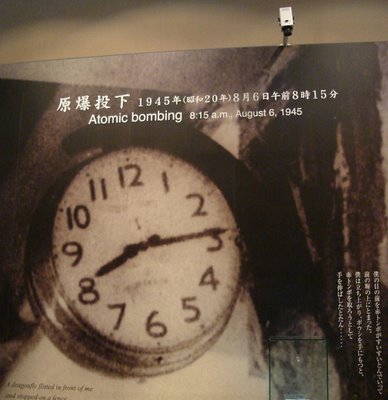

I'm not going to comment on the experience of the park, because my comments are largely cynical and colored by my frustration with Japan's weird anxiety over what happened in August of 1945. Suffice it to say, I spent a very long time looking at the following:

The peace museum is largely a photographic exhibit; sure there is the occasional mangled piece of metal or human body part (not kidding there), but the exhibit mostly contains some of the most breathtaking photography ever produced including an amazing panoramic view of the city which I'm convinced must be a composite and yet shows none of the signs it is.

But I spent most of my time staring at this photo, which Colleen continues to insist is not a big deal. It probably isn't, but it has for me what Barthes referred to in Camera Lucida as a punctum, though in reality I think it has 2 puncta: one a feature of the digital photo and the other of the photo in the photo. The former is the video camera looking down over the glass case which contains... I really don't remember what. It's odd to me that I care more about its gazing than the object thereof.

The second punctum is the time on the watch. The museum itself is saturated with precise dates and times, and featured prominently therein is the collection of watches the musueum has whose works were all stopped at the moment of the blast, 8:15 AM.

The watch in the photo reads 8:14 right on the button.

Much farther away lies Nagasaki, that other target, which peculiarly never seems to enter any Japanese rhetoric about the bomb. It was a secondary target chosen instead of the munitions depots at Kokura, because cloud cover there precluded the American command's insistence on a visual attack. Why the visual attack? So the surveillance aircraft accompanying the bomber could get better pictures.

And just one little postscript:

The target committee of The Manhattan Project unanimously agreed that Kyoto should be the first primary target so as to maximize the psychological impact of the weapon. But, as we all know, Kyoto basically escaped destruction of any kind, even though most Japanese cities were leveled or suffered significant losses. Then Secretary of War Henry Stimson had vacationed there on his honeymoon.